The Interviews

Cal Hyland

My family is from Cork, the Yorkshire of Ireland, and we believe it is the best place in the world. One of our greatest Cork men, Robert Gibbings, whose works I collect, would always insist that he was a Cork man first and an Irishman second. Cork was a great mercantile centre, providing victuals for the boats in its large and sheltered harbour. It was said that the entire British fleet could fit twice into Cork Harbour. It was also a very intellectual city in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, with numerous educational and literary institutions. Dublin, the political centre, was always regarded as the Johnny come lately.

When I was about seven years old, I had thoughts of joining the priesthood, until it was pointed out that I could not expect to become a bishop straightaway. As I was later to discover, it is the same with the book trade; you must first acquire an education through experience. During my school years, I was rather rudderless. My father was an agricultural scientist, and wanted me to become a scientist or to join the Army. I failed to achieve either of his ambitions for me, and drifted into office work of one kind or another.

There was a considerable economic slump in Ireland during the 1950s and in 1957 I came over to London to look for work. I hitchhiked my way to Dublin and got the boat over to Liverpool, and then down to London where I found a job on the buses. I started off as a conductor on route 31 from Chelsea to Camden Town – I can still name all the stops. By chance my driver was also from Cork. Routes 22 and 19 were good fun because they have the same journey for part of the way. We would race each other, and go twice round Piccadilly Circus and generally do things that would not be possible today.

In 1958 there was a bus strike and I found that I could not live on strike pay. I got a job in the royalties department of Chappell’s the music publishers and spent a year with them. By April 1959, having been two years in England, the Queen came after me to shoulder a musket. As I explained to the recruiting sergeant, ‘I came over from Ireland looking for employment. You had jobs which you wanted filled by people like me. We are now in a state of equilibrium. If I devote two years of my life to your Army, I’ll be placing you under a debt which you will never be able to repay.’ I do not think he quite saw my philosophical point, but I got off quite lightly and spent six months working on the buses in Jersey.

Back in London again, I found a job mixing Christmas puddings for Lyons tea houses. From 1959 to 1966, I worked in various capacities in the City. In my spare time I used to love dancing. I belonged to a Catholic social club in Westminster, and it was there that I met Joan, who was a nurse and also from Ireland. We got married in 1963.

All the while I had been accumulating books given to me by family and friends. I have always been a voracious reader. As a child I could not go to sleep at night without reading. I have great curiosity, and can appear to talk sense about quite a number of things. I used to spend a lot of my time at Speakers’ Corner, and generally make a nuisance of myself. I do not like people with extreme views, whatever they are.

I had an Irish friend at the time who worked in Oppenheim’s bookshop in South Kensington. He had gradually put together a list of Irish books, which he sent off to the trade in Dublin. His employers got wind of this and insisted on a share in his business, to which he replied, ‘No thanks’, contacted me and we became partners in bookselling. By that time Joan and I had our first daughter, and my mother helped us to move to our first house, which was in Belvedere, in those days a pleasant suburb of London on the south bank of the Thames. By that stage I was managing an office for a firm of steel fabricators. I would work on books from 6.30 to 9.00 in the morning, cycle to my employment, home for tea at 5.30 and then back to the books till past midnight.

At weekends I would visit somewhere like Guildford or Brighton, where there was a concentration of bookshops. Every fortnight or so, my partner and I would type up a list of twenty or thirty books, have the list xeroxed at my office and send it out to the trade in Ireland. After a while an Irish bookseller asked if he could visit us during a buying trip to the UK. This prompted Joan and me to cash in some shares in the company for which I worked and put the money into the business. I took a holiday and went on a spending spree, my partner and I setting off in opposite directions to buy stock – he went west and I went to East Anglia.

In the mid-sixties there were several secondhand bookshops in Norwich. I remember Mrs Cubitt’s Westlegate Bookshop, on several floors, with notices in the upper floors warning customers not to stand in the middle of the room. The floors bowed alarmingly, but for the brave there were rewards. Derek Gibbons’s shop was also rewarding, but he refused my payment by cheque – a nasty experience with a rascally Irish bookseller had coloured his view of the Irish trade.

In the event a bank strike hit Ireland and the promised bookseller did not come over. Meanwhile I had a lot of stock and an overdraft. I sent a list to a few institutions gleaned from The World of Learning, and the University of Texas at Austin ordered a considerable quantity – fourteen parcels to the value of £183. 10s.3d – riches untold in those days. Judge my dismay a few weeks later when I switched on the television news and saw a rifleman taking pot shots at passers by from the clock tower of the University of Texas at Austin. One of the victims was a postman... After three weeks on tenterhooks, my nerve broke and I wrote to Austin. My books had arrived safely and unbloodied, but I did not relax until the cheque came through.

Not long after, I had a very nice letter from Michael Walshe of Falkner Grierson in Dublin, advising me that the books they required were more specialised than I was offering, and suggesting that I sent my lists to Dr Eamon Norton of Wakefield – my first private customer. Eamon’s system was to read catalogues over breakfast, and then ring booksellers between seeing his patients. I am convinced he knew the opening hours of every book cataloguer in Britain and Ireland. To sample the hospitality of Dr Norton and his wife Dorrie, and to gaze at the world of Irish books in their beautiful Tudor house in Wakefield was an experience for any bookseller who thinks he knows it all. The latter tends to know the price of everything and the value of nothing, whereas the collector knows the value, and the why of the value.

There was a book published in 1907, William Bulfin’s Rambles in Eirinn, which includes a description of Gogarty and Joyce’s famous stay in the Martello tower in Sandycove in 1904. Although the first edition is quite scarce, it had passed through my hands a number of times before a collector pointed out that it contained almost the identical opening, certainly in terms of atmosphere, to Ulysses, which was published in 1922. I love these little bits of ancillary knowledge.

I was fast reaching the stage as a part-time bookseller when I was little use to my employer or myself. A board meeting with the managing directrix produced a decision to go full-time as a bookseller. Joan would supplement the family income with a bit of night nursing, as required. At my farewell party in 1966, my employer gave me this parting advice – always remember that stock is better than money. I have followed that dictum with ensuing tearing of hair by bank managers. By mid- 1967 I had parted company with my business partner, and was working on my own from our house in Belvedere. I had no shop; all I needed was my daughter’s pram in which I took parcels to the post office.

Through advertising in The Clique and The Book Market, I got to know a number of runners, who attended auctions and jumble sales and bought books with people like me in mind. One such traded under the name of Gerald Haydon from crummy Crumpsall in Manchester, as he called it. His real name was Gerald ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson, and he was a postman. On one occasion he offered me a copy of Yeats’s The Countess Kathleen, one of thirty copies printed on Japan vellum for presentation to his friends. Hutch had found it at a local auction, lotted up with other volumes. As old Mr Morten of Didsbury was present, Hutch disguised his interest in the bundle – Morten would immediately check a mixed lot if another dealer showed any interest. Hutch entered a modest ‘half-crown’ bid, which was accepted. I sold the book on his behalf and got him close to £75 for it. It’s worth a bit more today...

On a trip to the West Country I met R.A. Gilbert of Bristol, who was also giving up his day job as a teacher and going full-time into books. The Gilbert/ Hyland friendship has been of great benefit to me. Bob is the most knowledgeable bookseller of our generation. He could spot an Irish book at fifty feet. Bob was a non-driver in those days, and I took him down to Barnstaple with me where we met Gerry and Sue Mosdell of the Porcupine Bookshop. Gerry joined us on a trip to an extraordinary bookshop in the old cinema at Ilfracombe. The upper floor had no lights and Mr Smith, the proprietor, would give customers a torch, but he only had one. Gerry had sufficient local knowledge to come prepared, but I had to go out and purchase a torch. In later years, there was a man who used to attend PBFA fairs in London who wore a miner’s hat with a lamp on it.

I was one of the early members of the PBFA. It was Gerry Mosdell’s idea – he wanted to provide a regular ‘shop window’ in London for provincial dealers. When he was looking for a suitable location for holding the monthly fairs, he used to stay with us in Belvedere. The PBFA did not begin officially until 1974 when we were back in Ireland. Michael Holman of Angle Books was the first Treasurer of the PBFA. We were a bunch of school boys at heart, and the early book fairs were a lot of fun. But they were also one of the biggest factors in changing the popular perception of bookselling, and the travelling book fair became a great source of education and inspiration. It brought a lot of new people into the trade, though of course not all of them have survived.

Late in 1967, I responded to the following advertisement in The Clique,‘Specialist Bookseller would like to meet another with own transport, with a view to sharing expenses on buying trips’. I responded and met Eric Bonner, with whom I made a number of trips in my secondhand Commer Cob van, with its back seat that folded down to make a bed. The Cob was a real goer and 80 mph was easily done. Our first trip was to Northampton, Leicester and Nottingham. I slept in the van and Eric, who was of an older generation, stayed in hotels.

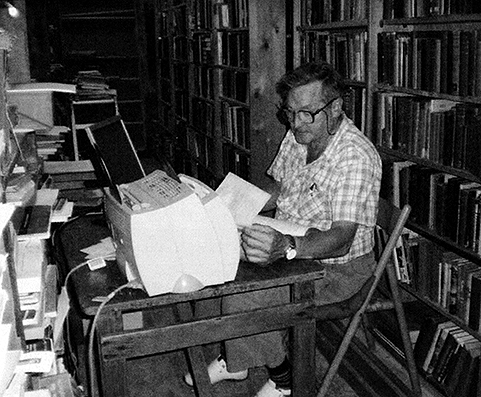

By this stage Joan and I had two daughters and began to have thoughts of raising them in Ireland. A family opportunity arose to bring us to Dublin and we made the move in 1968. I had a large bookstore in Dun Laoghaire, with shelves made from wood salvaged from the demolition of the old Garda headquarters at Dublin Castle. Neville Figgis of Hodges Figgis involved me in a number of large purchases, and he and his right-hand man, Padraig O’Tailliur, were an invaluable source of information.

Michael Walshe had done a lot of cataloguing for Hodges Figgis before founding Falkner Grierson. He had introduced me to Dr Norton, and was another Dublin bookseller who was very generous with his vast knowledge. The name of Michael’s firm derived from George Faulkner, publisher and friend of Jonathan Swift, and Grierson, government printers in Dublin for several generations. The name therefore combined two firms famous in the Dublin book trade. Michael had a delightful sense of humour and used to produce highly comical material on his own printing press. His fictitious correspondence on the ‘de Selby Codex’ in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman is a real gem. The mists in Ireland encourage us to fall back on our imagination. You cannot look out of the window and see the horizon. Perhaps this has inclined us to creative writing.

Greene’s Bookshop in Clare Street was the place where the Dublin literati had been gathering since the mid-nineteenth century. It was my idea of a perfect bookshop – there would always be someone there holding court, who could talk knowledgeably about books and encourage others to share their interests. We all know the story about people who would go through the new arrivals at Foyles, buy something for a couple of shillings, climb upstairs to the rare books department and make a couple of hundred pounds. To me that style of bookselling is soulless. I find most affinity with customers who read the books they buy from me, or with librarians who consider the needs of their readers.

In 1972 another daughter came on the scene and the house in Dublin was getting a bit crowded. A lovely old rectory came on the market a quarter of a mile from Joan’s birthplace and eight miles from my home town of Mallow. We purchased it and moved in during the month of February 1973 – one pantechnicon a week, each with about 100 tea-chests of books. The rectory had been built by Ernest Shackleton’s great-grandfather. It had twenty-two rooms, of which seven were filled with my books.

I used to produce about ten catalogues a year on books of Irish interest. It was a family affair; we printed them ourselves on a Gestetner offset litho machine. One of my daughters would watch the machine, and be ready to switch it off at the first sign of a paper jam or any other trouble. However the ‘good life’ became a tad less than idyllic with postage increases of 120 per cent during the Cosgrave coalition government in Ireland, and the huge increase in travelling expenses caused by the oil crisis in the second half of the 1970s.

The 1970s also saw a marked decline in my business with the north of Ireland. I used to be able to count on £20,000 a year in sales to libraries and collectors in the six counties. As a result of the political problems, money increasingly had to be spent on security arrangements. Two days before I was due to deliver a large order to Fermanagh County Library, the building was badly damaged by a car bomb. Nowadays I consider myself lucky if I do £1500 a year in business with the north of Ireland. The mind-set has changed considerably. The old-style county librarian no longer exists, by which I mean someone who had an interest in local history and perhaps belonged to one or two antiquarian societies. The new-style librarian is likely to be trained in information technology and accountancy.

By the mid-1980s the older Miss Hylands had both returned to the land of their birth in search of work, leaving their middle-aged parents and a teenage sister in a large house with a two-acre garden in the middle of nowhere. This was no good for a teenager’s social life, and none of us had much interest in gardening. We made inquiries and discovered that the economic climate for small postal businesses was more congenial in the UK. We moved to Chepstow in 1986, and spent several years there before moving to beautiful West Cork, where we had been spending family holidays since the late 1960s.

We purchased a bungalow in Rosscarbery and in 1996 we opened Pilgrim Books. The old Irish name of Rosscarbery is Ros Ailithir, which means ‘The Headland of the Pilgrim’. In the summer of 1998, the eldest Miss Hyland returned from London where she had been running bars and bistros. We decided to purchase a restaurant and she joined her aged parents in running Pilgrim’s Rest, a bookshop/bistro combination. Rosscarbery is a holiday resort and during the months of June, July and August, we were open seven days a week. Our daughter did the cooking, my wife did the baking and I did everything else, as well as running the bookshop. I would sit by the till with a glass of wine and, if anyone commented, I would say that it helped me to overcome my natural shyness.

After five years of hard work and good fun, we had to surrender to anno domini. We sold the premises and moved to a development on the outskirts of Rosscarbery. By purchasing the lower floor apartment (under two uppers), we were able to create a perfect book room, which runs the length of the properties. The books are on all aspects of Ireland, with a small selection of non-Irish material, and visitors are most welcome by appointment. I consider myself extremely fortunate. I have made a competence, raised a family of three daughters and enjoyed myself making a living of my hobby – and making friends. I would not like to re-write any of it.

Interviewed for The Bookdealer in October 2009

Afterword

Last year, having passed my 82nd birthday, I sold my stock, lock and barrel, and am now an unemployed bookseller. Such knowledge as I have is available, and my contact details remain the same: 4 Closheen Lane, Rosscarbery, Co. Cork. Tel: 00353 238848063, mobile: 00353 872349778, email: calbux@gmail.com

Since 2012, Joan and I have been researching the files and minutes of the Irish Distress Committee and Irish Grants Committee in the British National Archives.

We sent over 1,000 corrections to the online index, which were gratefully accepted and the changes were made very quickly. Most of the errors were typographical and transcriptional, the original work having been done by people unfamiliar with Irish personal and place-names. We have a bank of 16,000 photographs, mainly of the claims forms themselves and some extra documents, which we felt might usefully illustrate the claim. That is our pension supplement.

Afterword added in March 2018