The Interviews

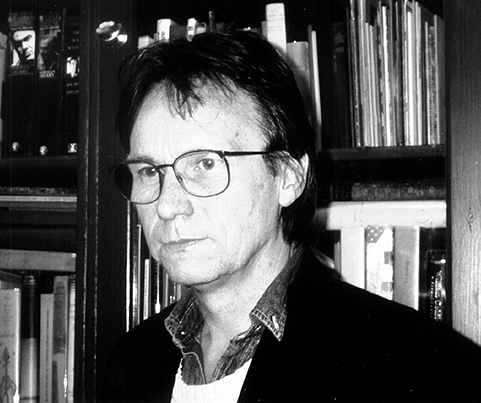

Julian Nangle

The money side of bookselling has always rattled too loudly for me. Originally I wanted to become a publisher. I had taken to writing poetry and thought it would be great to edit poetry – and publish my own. When I failed to get into publishing, my mother sweetly rang up Charles Traylen behind my back. He told her that there was a vacancy coming up at Quaritch. In fact it was next door at Chas J. Sawyer, which I joined in the autumn of 1967. During the interview, Raymond Sawyer had asked me how much I thought I was worth. I remember thinking it was a very unfair question to ask a twenty-year old, and agonised whether I dared go into double figures or not.

On one level it was a very exotic and enjoyable experience for a young guy starting out in the book trade. Chas J. Sawyer was central to what was going on in London in the ’60s. I remember delivering two boxes of signed Rackhams in full morocco to Jean Shrimpton. George Harrison came into the shop and said to me, ‘Dickensian, isn’t it ?’ Wilfred Thesiger and many other fascinating people were also customers. On another level, it wasn’t the poetry inside the book that mattered; it was the money that the book represented.

After eighteen months at Sawyer’s, the money was really beginning to rattle. I decided to have a short break in France where I had spent a year after leaving school, and had discovered a fabulous bookshop in Paris called Shakespeare and Company. It was owned by George Whitman, an ex-pat American who claimed to be the illegitimate great-grandson of the poet. I went back and asked George what he would say if I presented myself for work. ‘Fine’, he replied. ‘There’s a bed upstairs and what would you like for supper tonight?’ I explained that I could not come at once as I had to give in my notice at Sawyer’s.

George Whitman’s shop was originally called the Mistral Bookshop, which opened in 1952. He changed the name when he realised that Shakespeare and Company was up for grabs. George belonged – at least in his heart – to the American ex-pat scene in Paris in the ’20s and ’30s. He wanted to continue the spirit of Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company, the bookshop on the Left Bank that became a literary crossroads. It was a meeting place for people like Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Durrell. George kept on the tradition of poetry readings in the shop. He would throw a match into a well that he had constructed in the middle of the shop; it would burst into flames for a few seconds and this marked the beginning of the reading. One of the greatest joys in my low-key poetic life was giving a reading at Shakespeare and Company.

Having given in my notice at Sawyer’s, I spent six weeks working for George Whitman. I could not stay any longer, as it was part of a deal that I had made with my father. He was head of a big accountancy firm in the City. Poetry is not something he can relate to and I doubt if I have ever discussed it with him. I can’t remember if his firm did Christie’s accounts, but he managed to pull a few strings and lined up a job that he wanted me to take in the Book Department. I managed to stick it out from 1969 to 1971.

Dudley Massey was head of the department – a rather frightening man and a bit intimidating to work for. Luckily I struck up a close friendship with a colleague, Frank Lissauer, who was also a poet and took me under his wing. He catalogued the scholarly books and I dealt with the modern first editions, which appealed to me because of their association with living people. There was a girl working in the general office and we went to Paris together for Easter in 1971. George Whitman had promised me a bed for life and so we stayed at Shakespeare and Company.

While we were there, an American journalist, en route for Vietnam, asked if we would give him a lift in my mini to India. We made up our minds on the spot and decided to give in our notice at Christie’s. (Two months later a management consultant recommended that all the staff should have an 80% pay rise). In the event we didn’t go to India but, as we had the car, we travelled around Europe a bit. My friend had a girlfriend with her and they decided to stay on in Rome. I went back to Paris where I met Edith, my wife to be, studying for her baccalauréat in the upstairs room at Shakespeare and Company. We were not the first couple to meet there.

Edith wanted to live in England and so we moved into my parents’ house for a while. I found a job nearby in Haslemere at the Crane Bookshop, as it was then called. It was a very attractive shop, which belonged to Bertram Rota and was run at that time by Richard Budd. Dick was on the point of setting up on his own and I took over from him. Rota’s used to send all their literary periodicals down to Haslemere and I would index the contents and produce catalogues. It took an enormous amount of time but was very enjoyable.

George Lawson came down once a week to take me out to lunch and to check that everything was going all right. On one occasion he told me that someone wanted to make me a partner. In actual fact Rota’s had sold the Crane Bookshop to Ian MacDonald, who had a background in advertising, on the understanding that I would stay on as manager. The deal to keep me in was to make me a partner and to offer me a quarter of the equity in the shop after two years. I agreed on condition that my wife could be an assistant.

The arrangement worked well for a year. Then one day MacDonald came in and threw a catalogue on my desk, saying, ‘This is what you should be doing’. He claimed that it had been put together by his wife, when in fact he had employed somebody behind my back to go round the country buying books, and to produce a catalogue for the Crane Bookshop. He also announced that he was getting rid of the entire stock of periodicals – knowing that I loved them more than anything else in the shop. On the spur of the moment I said, ‘You can’t do that. My mother wants to buy them’.

MacDonald wanted to drive me out before the two years were up, and he succeeded. I resigned in May 1974, almost a year before I could claim my quarter equity. My first catalogue was full of the literary periodicals that I had bought ‘through’ my mother. To keep up the pretence, it was issued in her name, Margaret K. Nangle.

Catalogue Two was issued as Julian and Edith Nangle, and later catalogues as Words Etcetera. Our first child was born a few months after the second catalogue. We were living in a flat in Godalming and it was a very busy time. Having been a partner in a business that was effectively sold to Ian MacDonald and myself, the mailing list was part of that sale and I made sure to take a copy of it. We were able to hit the ground running, and I banged out catalogues on an electric typewriter till eleven o’clock at night for several years.

In those days there were perhaps no more than five or six specialists in England in modern first editions. The dust-jacket was less of an issue than it is to- day. I sold thousands of first editions without them. I would prefer to have gone on selling copies of A Burnt-Out Case, with no jacket for £15. One can find them and be of service to the majority of people who can’t afford to pay top prices.

If I have a hero in the book trade, it’s Peter Howard of Serendipity Books. On one occasion when I was in his shop in California, he remarked to somebody else, ‘You must not forget about the $2 books’. Then he looked at me as much as to say, ‘You understand that, Julian’. In fact it encapsulates my philosophy of book- selling. Don’t forget the cheap books or the people who are able to buy them. So many dealers spend their time running after books that only mega-rich people can buy. This was certainly true in the mid ’80s when everyone was chasing the next copy of Metroland. Maybe it was the sound of money rattling again that made me produce a magazine called Slightly Soiled. The first issue featured a cover with a microphone and an upright coffin, inscribed ABA. I managed to produce one more issue before the backlash became too much.

In 1975 we moved to London and found a grocer’s shop in Islington that had been empty since 1944. I turned it very quickly into a bookshop, varnishing the bare brick walls to keep down the dust. Curiously we took £6,000 across the threshold for each of the three years that we were there – it never changed and the catalogues helped us survive. I also organised poetry readings that went very well, and people like Stephen Spender and Ted Hughes came.

Then in 1978 everything changed for me. My wife left and I basically retreated into myself. I write more profusely when unhappy; 1978 was my most productive year. The business was kept going, for which I am particularly grateful to Lizzie Graves for all her help. She is the niece of Robert Graves, and had been working for the Basilisk Press. I wrote my first Personal Note – a feature of my catalogues – in Catalogue 50 as a way to acknowledge publicly my gratitude to Lizzie. At the end of 1978 my wife came back briefly. We moved somewhere else in Islington and I soon discovered I could not afford it. We finally agreed to split and my wife returned to France with our children. I went to a cottage near my parents’ house, where I produced catalogues for a year or so. When my brother’s flat became available, I moved back to London. The flat was conveniently located for the French Lycée and it occurred to me that it would be ideal for the children if they ever returned to England, as indeed happened.

During this period I shared an office in Fulham Road with Peter Jolliffe. When the rent doubled in 1986, it was time to move out of London again. I had recently met my second wife, Anna, and, between us, we had five children aged from three to twelve. I rang around a few estate agents, and Dorset turned out to be the cheapest county for houses large enough to accommodate all of us.

We lived in a house near Blandford Forum until the boys grew too tall for their attic rooms. I opened a bookshop in the High Street and five months later Tesco supermarket opened out of town and Blandford just went to sleep. I struggled on for a year before closing. Meanwhile I had opened another shop in Dorchester on four floors. In the last year I have also opened shops in a better location in Blandford, in Bridport, Weymouth and in Museum Street. I know to my cost that location is all-important – God knows how much better the Bloomsbury shop would do in Great Russell Street. But I find Museum Street more romantic.

I may be perceived in the trade as someone always on the move. Actually my moving is basically motivated by family considerations. I opened in Museum Street because two of our children have just started university in London. They can work in the shop and that will help all of us. It was always my dream to do things in a shared way. Lifestyle is so much more important than money. Anna is also becoming involved in the business, although she has her own practice in the field of complementary medicine. Indeed for the last ten years I have had a practice in psychotherapy, which has proved a very effective balance to bookselling.

I have contracted the business down to one bookshop in Dorchester and to selling books on the Internet from my home in Spain. Air fares to Malaga can be cheaper than train fares to London and frequent sally-forths into the British book scene can provide all the fodder I need for the shop in Dorchester and for my catalogue and Internet business. The weather also featured in my decision to move. Life is one long experiment – next year it could be ... Slovenia?

Interviewed for The Bookdealer in December 1999

Afterword

I now seem to spend as much time writing poetry as I do reading it and trying to sell it. As I get older poetry seems to be becoming more and more important to me as a source of creativity if nothing else. I find the death of friends and the recollection of events in my life cannot be ignored poetically. Thus I have written two poems in the past year that are set in a bookshop, one relating to when I met George Harrison in the very first bookshop I worked for (Chas J Sawyer, in 1967), and one when I met (and sold a book!) to Seamus Heaney, in my own bookshop here in Dorchester (in 2005, both now gone sadly – I sold the shop in 2006 and the new owner went bust within 4 years). I work from home now.

Afterword added in July 2017