The Interviews

Nigel Burwood

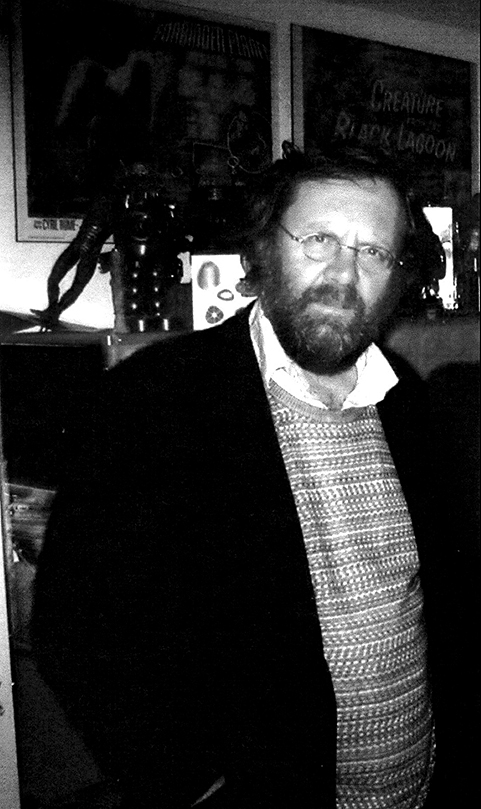

I began collecting books while I was still at school, and went on to read English Literature at Southampton. It was considered a very unsensational university. In fact a friend of mine who worked for Condé Nast asked me to contribute to an article on the theme of really dull universities. Actually I enjoyed it there. My professor was F.T. Prince, a Second World War poet who had been quite an influence on his generation. He had known people like Eliot, Auden and Spender, and I subsequently bought some wonderful books from him.

After university I did a variety of jobs, including teaching, though not at a minor public school, as people do in novels. I wasn’t cut out for it and before long I took a barrow on the Portobello Road and began selling my books. This was in 1975, about the time when Charles Russell, Nick Dennys, John Adrian and Driff were also there. The junction of Portobello and Golborne Road became a slightly raffish book corner.

People would come up to my stall and ask for Rackham, Dulac, Nielsen, Sven Hedin, Aurel Stein, and I soon learnt the names of saleable books. Obviously the trade is more difficult than that, and the clever thing is to know where to find the books. I was excited by the possibility of making a special discovery. One of my first customers found a Thomas More manuscript on George Jeffery’s barrows in Farringdon Road.

After a while I got tired of stalling up every week and opened a shop in Hammersmith. I soon discovered that it was an excellent location for buying books. Kensington High Street was not far away, and the area was full of interesting elderly people living in mansion blocks – I bought books from a woman who had known Nancy Cunard. There were other booksellers nearby – Peter Eaton in Holland Park, Jack Sassoon in Kensington Church Street and Bill Foster in Chiswick. But they were all very pleasant and I don’t remember any trade jealousy. In any case Peter Eaton was getting books by the truckload, and Jack specialised in children’s and illustrated books. He was a charming old fellow and all the ladies liked to deal with him.

Meanwhile I had my own fiefdom at the confluence of a rich area and bedsit land, and business was very good. But there was always a touch of planning blight about our block. A developer wanted to get us out and eventually did, although it cost him £50,000, which was a useful amount of money in 1984. Someone told me that there was a shop available at 62 , Charing Cross Road. It had been a slightly dubious video shop and a bookshop before that. I managed to negotiate a reasonable rent of £8,000 a year and we moved in. The shop was immediately terrifically busy. I hesitate to use the work ‘successful’, but we did sell a lot of books – you might say any amount of books.

Eventually I also took on 56, Charing Cross Road and ran the two bookshops together. But as the rent began to increase, the game became less worthwhile. I wanted to rent out one of the shops, but the landlords would only accept a certain type of tenant – preferably something unobjectionable like a craft shop. In the event they agreed to take back 62, Charing Cross Road and I’m now down to one shop at number 56.

You often hear people say that it costs a fortune to set up in the book business. All it really takes is the ability to pay the first three months’ rent. A bookshop is not like a restaurant where you have to work up the business, get some good reviews and attract a few celebrities. If a bookshop doesn’t work almost immediately, it’s never going to work. When you first open, you have the advantage of novelty and an unpicked-over stock. Of course, the right location is vital. The shop itself doesn’t have to be particularly interesting in appearance as the books will soon give it character. You need to have books outside, good books in the window and someone friendly at the counter. You should also try to arrange the books so that customers feel that there are things to be discovered. Never act superior or appear more clever than your customers. For a while I had a sign up for the benefit of the staff – but not visible to the public – saying, ‘Fools tolerated gladly’. Because of the Charing Cross Road address, a few Americans have tried to start up a correspondence with me. I’m afraid I can’t be bothered with all that, but I won’t knock Helene Hanff as she has brought us lots of business. We can sell any amount of copies of 84, Charing Cross Road. I remember Driff pointing out that Frank Doel had taken ten years to find a perfectly common book for her. Too busy corresponding, perhaps.

When I had two shops and a fast turnover, I could sell almost anything, buy large collections and make every part of them work. But in the new shop, I have to be more choosy, and learn not to buy certain types of books. We are keen to go upmarket a bit, to make deals and sell books to the trade. We give 20% discount, which is quite common in America. It’s a useful amount because, if the book is attractive enough, you can almost buy it just for the 20%. I go to America three or four times a year, mainly to New York and the West Coast. San Francisco and Berkeley are terrific book centres, and I like San Diego as a book town. The prices in Los Angeles always seem slightly greedy.

In England a book will usually state if it is a first edition, or it won’t mention any subsequent printing. But American publishing companies have their own complicated systems for identifying a first edition. If you’re scouting for books over there, it’s almost essential to have a copy of Bill McBride’s Pocket Guide. In America when members of the public have books to sell, they might call in four or five dealers, and sometimes still consider that they haven’t achieved the best price. They tend to assume that all old books must be worth a fortune or at least something, and are rather in awe of them. As a result, American dealers sometimes pay too much for their books. But on the other hand, they are quicker than we are to reduce the price if books don’t sell.

In England people tend to regard books – unless they are clearly very special – as something to be got rid of. This is often the attitude when people inherit a house, particularly in a place like London, where the value of the property is usually vastly more than the contents. In my experience of buying collections, it’s often a question of the level of expectation, the LOE as we call it. If this is too high, the deal is not worth wasting time on.

To me the price of a book is one of the most important factors about it. You can’t sell a book if you over-price it, unless you have very deep carpets and an unctuous manner. We have a saying in the shop, ‘The right price is the wrong price’. If you put the right price on a book, that’s about the price at which it won’t sell. It’s a law of economics, although bookselling tends to defy most of them. On the Internet you can find numerous copies of the same book, in similar condition, at wildly different prices. The dealer offering the most expensive copy thinks that his will sell when all the others have gone. This will never happen as cheaper copies are flooding in all the time. We tend to price our stock on the Net very competitively, either offering the only copy, or the most reasonably priced. This involves a lot of checking and we now have one and a half staff devoted just to our Net business.

It would probably have been better for the book trade if the Internet had never been invented: it has spread the game too wide. But because it has been invented, you have to join in. Our website attracts around 1,000 visitors a week. We use it mostly as a publicity tool, and it has produced a number of very worthwhile inquiries. We also receive our share of questions about the value, for example, of an odd volume of a set of the complete works of Browning, lacking the spine. I normally steer them in the direction of eBay.

The website includes a section entitled ‘Dogs I have Known’, and I receive suggestions from all over the world for my list of slow-selling, common used books. The biggest ‘dog’ in Britain is The Scallop, published by Shell in 1957. Copies were presented to every shareholder and, I suspect, given away at petrol stations. You will find hundreds of copies on the Internet, with some dealers even calling it a rare book. Over the years the top dogs have changed. When I came into the trade, there was a book by Virginia Woolf called Flush and it was literally a dog, albeit a biography of a dog. If anyone offered you a Virginia Woolf, it was always a copy of Flush. Today it’s probably worth £300, if you can find one.

Interest in modern English literature is mainly confined to a few authors – Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Ian Fleming, Ian Rankin, Agatha Christie, J.K. Rowling, and a handful of illustrators – Heath Robinson, Dulac, Rackham and Nielsen. Twenty years ago the list would have been much longer. Ian Fleming would still have been

on it, but so would Evelyn Waugh, Conrad, Joyce, Eliot, Pound – the great masters. Although they are still saleable today, a few fantasy writers have certainly pushed them to one side. Standards of condition also change. Evelyn Waugh still needs to be in fine condition, but a set of the Narnia books in chipped dust-jackets is still worth a lot of money. The change reflects the broader base of the book buying public. The film ‘Notting Hill’ probably made bookshops sexy for a while, and appealing to people who had perhaps never bought a book before. A colleague told me that he had been unable to sell a copy of The Hobbit, fine in dust-jacket, for £1,000 in the 1970s. Recently a copy changed hands for US$100,000. I believe that television and cinema will increasingly dictate taste in book collecting.

Interviewed for the Bookdealer in January 2002