The Interviews

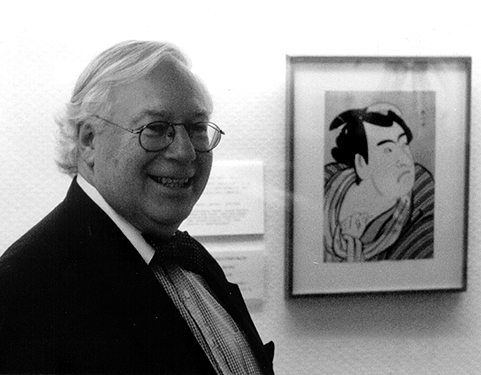

Robert Sawers

My story begins in 1947 when I joined Blackwell’s in Oxford as a book porter. Having failed various examinations at school, my headmaster wisely recommended me for this job. He knew that I loved books and was an avid reader. As for my academic failure, I realise now that I was dyslexic, which was rarely spotted in those days. I’m extremely grateful to him when I think of what the employment alternatives would have been – a job at Morris Motors, or something in a steel works where most of my school friends went.

Blackwell’s was a very cosy family business. Sir Basil felt that he was the grandfather of us all. Employees tended to marry each other. As none of them could afford a mortgage – they were paid so little – the money would be lent from the business. The porters had competitions to see who could carry the largest pile of books. We raced around the shop, dropping them off at the various departments – and occasionally from the Theology gallery on to startled customers below.

For a long time I was nervous about dealing with customers. Everything had to be learnt from scratch – The Frogs of Aristophanes, for example, was not to be found in Natural History. Slowly I built up my knowledge and became assistant to R.W. Gibson in the Oriental Department. Gibson was the great bibliographer of Francis Bacon and St Thomas More. Most of his time was spent in the Bodleian Library, and I was left with a fairly free hand to run the Department – and to make mistakes.

In an active university bookshop, I was only too aware of my ignorance. But after a few years, I found that I had a flair for remembering books. I was no longer hiding from customers and began to find that I could often answer their questions. In due course I was put in charge of the Hebraic Department and a tutor was organised to teach me Hebrew. One day I was struggling with a translation exercise when G.R. Driver, Professor of Semitic Languages in the University of Oxford, came to my desk and helped me finish my homework. He was a very charming man, as were most of my academic customers.

At first I was rather jealous of their knowledge and the academic way of life. But I soon discovered that it wasn’t a very happy world and there was an enormous amount of back-stabbing. I was in the Hebraic Department at the height of the Dead Sea Scrolls controversy. Blackwell’s had published a number of pioneering studies, and Semitic scholars around the world were adding their own commentaries and translations to the debate, and reviewing their colleagues’ books very critically. When they bumped into each other in the Hebraic Department, it was not unusual for fisticuffs to break out.

In 1958, an advertisement appeared in the Bookseller for an assistant manager at Kegan Paul. I was very happy at Blackwell’s and enjoying life in Oxford. The idea of moving to London was not very appealing. But I was contemplating

marriage and the salary of £500 a year was more than double what I earned at Blackwell’s. My wife pushed me to apply for the job and I got it. Sir Basil himself wrote me a charming letter saying that he hoped that the streets of London would be paved with gold.

Kegan Paul were the leading Oriental booksellers and publishers. Quaritch, Maggs and Francis Edwards were also dominant in the field, but none of them specialised exclusively in Oriental material. The firm had a wonderful building opposite the British Museum, and were agents for their publications. When I was in Oxford, I got to know many of the staff at the Bodleian – in fact, Stanley Gillam, of the Bodleian Library, was my Scout Master. At Kegan Paul I had a similar marvellous opportunity to meet curators at the British Museum.

One of the hardest jobs to fill in a book business is the packer. Kegan Paul never paid enough, so we never had a good one – despite the fact that it was such an important job. One day somebody applied for the job and was shown up to my office. I could not believe my eyes when in walked David Lincoln. He had been the chief cataloguer of rare books at Blackwell’s. You could frame his catalogue cards – they were so brilliant and beautifully written. But he had fallen on hard times and had a nervous breakdown. I explained that I could not possibly have him packing for me, but asked if he would like to do some cataloguing. The result was a stream of excellent catalogues, including Kegan Paul’s African Quarterly, which was one of the best in the field.

I had looked after Africana at Blackwell’s and, by the time I got to Kegan Paul, the subject was ready to take off. The Americans were starting to worry about ‘Reds under the bed’ in Africa – the Chinese had moved into Ethiopia, and there were unsettling Russian movements. The US administration became extremely generous with university grants for African studies, with the result that you could sell ten copies or more of any book with Africa in the title. While I was at Kegan Paul, the library of Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone came on to the market. A nineteenth-century Governor of Bombay, Elphinstone had accumulated a great Orientalist library, which was sold by Sotheby’s at the family seat in Scotland. I spent a fortune at the sale to the horror of Mr Cole, the manager, who said, ‘You bought them, you sell them’. I had hardly finished unpacking the books when someone from Northwestern University came in and bought the lot. From that moment my reputation went up in Mr Cole’s eyes.

Kegan Paul also specialised in Japanese prints – in fact they were the biggest dealers in this country together with Bluett. The odd thing had gone through my hands at Blackwell’s, but we were primarily academic booksellers. As I was soon to become manager at Kegan Paul, I had to learn about Japanese prints, illustrated books and paintings as fast as I could.

It was an extremely fortunate time to enter the field, just as interest in Japanese art was beginning to revive after the War. In the ’50s and ’60s, you could go to an auction almost daily and find good quality Japanese prints for sale. I learnt as much as I could by watching my boss handle and discuss them with clients. I had to find out what these grimacing actors and other strange subjects were all about. You can read as much as you like, but you learn best by dirt under the fingernails. The ability to tell a fake from a genuine print takes years of handling them – learn- ing how the colours fade, the feel of the paper and other physical details that have to be retained in the memory.

But I held one ace in my hand – my friendship with Jack Hillier, author of The Art of the Japanese Book, and Sotheby’s expert. Jack came to Kegan Paul once a week for lunch at the Museum Tavern. In return he would tell us anything we didn’t know about Japanese prints and drawings in our stock. He had been a woodcut artist himself and, realising the difficulty of the medium, had come to appreciate the Japanese skill in perfecting the art. An insurance underwriter by profession, Jack became one of the great experts on Japanese prints. I had the privilege of being with him when he catalogued the Stoclet collection of Japanese prints, sold by Sotheby’s in 1965. Jack also introduced me to the field of Japanese illustrated books. At the time it was a totally neglected subject in this country. Kegan Paul had a room full of wonderful treasures, which Jack catalogued, and I learnt a lot in the process.

Kegan Paul also had a big Islamic section at just about the time when oil money was starting to hit the art market. I was slightly tempted to specialise in this field, but I soon found that Middle Eastern clients could be difficult to deal with – particularly compared with the Japanese. The negotiation may be tough, but when a deal is agreed with the Japanese, you can rest assured that nothing will go wrong. It was also a case of concentrating on a field in which you could trade at a high level. At that time prices for Islamic art were higher than for comparable Japanese art. In the event my friendship with Jack Hillier had to be one of the deciding factors.

I can’t say that I never had second thoughts – especially when I saw the prices fetched at auction for Qajar paintings in the 1980s. We had sold them at Kegan Paul for a couple of hundred pounds a time, and then to see the same painting fetch £80,000 fifteen years later.... But I have grown to love Japanese art and have made so many good Japanese friends. I first visited the country in 1968 and have been back more or less every year since. I can now speak Japanese reasonably well – at least so that I don’t go hungry.

After twelve years at Kegan Paul, I was made an offer that I couldn’t refuse. Bill Jansen, a Dutch friend and great collector, lent me £50,000 to start my own business. We had a deal whereby he had first refusal on anything I bought plus 10%. This arrangement helped me to get started and to pay back the debt.

First of all I bought a house in Camden Square for £9,500 – the smartest thing I ever did. (It has since changed hands for over £1m.) By then I was divorced, but had my four children living with me. They were tough times domestically. Fortunately all my clients at Kegan Paul were friends and they remained with me, and so things have continued to this day. I have always managed to deal with clients in an amiable way and it’s been very valuable in business.

During the mid ’70s Sotheby’s sold the Vever collection of highly important Japanese prints, illustrated books and drawings. We hadn’t seen that quality of material on the market since long before my time. At one of the sales in 1974 I had a budget of £20,000 to spend. By the end of the sale, I was shocked to see that my bill came to £117,000. I didn’t sleep that night. The Vever sales marked a huge jump in the prices of Japanese prints and drawings. In fact we haven’t really seen a group of similar quality fetching such huge prices since that sale. Due to economic problems in Japan and, more recently, in America, prices have levelled off significantly. Japanese institutions have suffered a drop in income. But if you find an exceptional item, there is no problem selling it to them – very good is no longer enough.

Hiroshige has paid my rent ever since I can remember. He was one of the most prolific landscape artists and a member of the popular Ukiyo-e School. His prints probably pay the rent of dealers round the world. Because of the scarcity of the early prints, later examples are becoming quite sought after. Yoshitoshi, an artist from the Meiji period, has become very popular. But some of these later prints are a little too violent for me. I’m 68 and I find that I can’t get much past 1868 in my taste. This was of course the great turning point in Japanese history, with the opening of the country to Western influence. Modern printmaking in Japan is mostly so westernised that you might find it hard to guess the artist’s nationality.

The Japanese don’t understand how a guyjin (foreigner) can appreciate Japanese prints. But I believe that we can all respond to the same qualities of design, colour and impression in a fine print in fine condition. Indeed there was a time when the Japanese had less regard for their own prints, and were greatly influenced by the growth of Western connoisseurship. Frank Lloyd Wright mopped up prints by the thousand when he was in Japan building the Imperial Hotel. This partly explains the American strength in Japanese print collecting. The Swiss were also very big collectors – I suppose the explanation is quite simply money.

The Japanese dealer Hayashi did much to establish the European taste for Japonisme by bringing prints to Paris, where they were immediately appreciated by the French Impressionists. The tradition of collecting Oriental art in England was always focused on ceramics. We are only catching up slowly in the field of prints and paintings.

Apart from Jack Hillier, the other important person in my career was Colin Franklin. He became director at Routledge, and was given responsibility for Kegan Paul. When the company went public, Colin astutely sold his shares and became one of the great rare book dealers of our time. He has been a great patron and a marvellous friend and, over the years, has built up a fine collection of Japanese books and manuscripts with huge taste. Last year The Book Club of California published Colin’s book Exploring Japanese Books and Scrolls, and I’m delighted to have a copy inscribed to me, ‘without whom this book would not have been born or thought of ’.

I was so lucky to enter the business when it was still possible to buy and sell a lot of good material. In some cases I even had the luck of finding exceptional items without realising it at the time. My greatest find was in a shop in Kyoto where I spotted nine panels from a screen decorated with banana leaves. They were badly worm-holed and I had no idea where they had originally come from. But I guessed that they must have been made for a temple or castle. One day I had a visit from Tim Clark of the British Museum and a party of young curators from Japan, one of whom was able to identify the provenance of my panels. Tim advised me to sit down before he told me that they came from Ryoanji no less, one of the great temples in Kyoto.

At the time of the rise of the military in Japan in the 1890s, Ryoanji had to sell all its fusuma (sliding screens) as it was desperately short of money. They were bought by Higashi Honganji, another great temple in Kyoto. They in turn sold them to Mr Ito, a rich Japanese politician who exhibited them in 1934 at Osaka Castle to commemorate its 300th anniversary. When the War came, the works of art were stored in the basement of the castle. The American Navy took over the castle after the War, and the Japanese were given two days to vacate it. The screens were left behind, possibly because they didn’t belong to the castle. Eventually they found their way on to an American battleship, and various panels began turning up here and there all over the States. The examples in the Metropolitan Museum of Art were found in Florida, and the Japanese dealer from whom I bought my panels had found them in Dallas. I still own them.

Nowadays the market is rather like a bath – once it was full of water, but as the level drops it drains faster. At the moment we are spinning around the plughole. A living could still be made in the field of Japanese prints and drawings, but it would be harder than it was for me.

Interviewed for The Bookdealer in September 2001