The Interviews

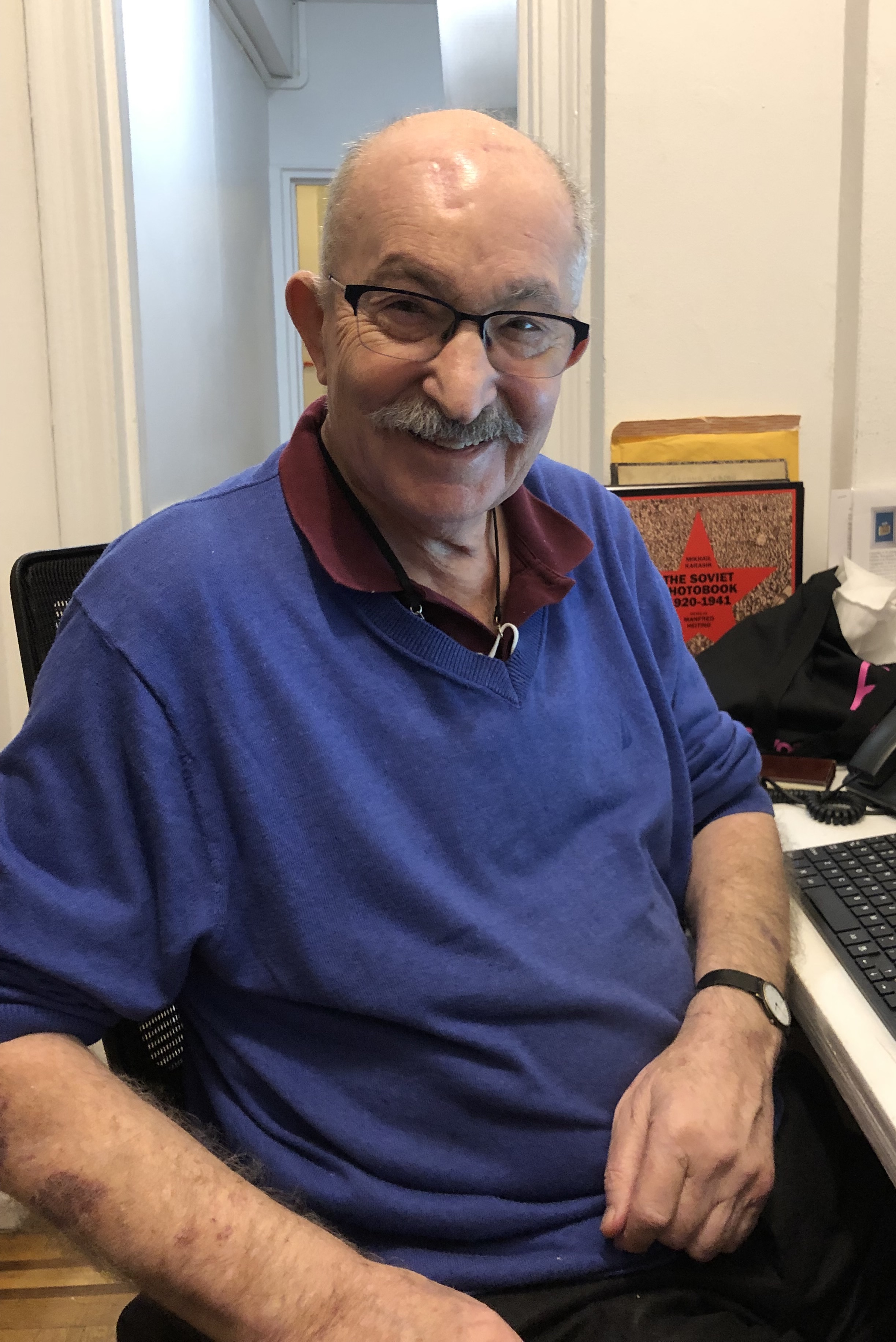

Peter Kraus

The story begins with two brothers who married two sisters. H.P.Kraus was the son of one couple, and the other couple gave birth to my father. Although HPK wasn’t really an uncle, I always called him Uncle Hans, and regarded his children as my cousins. Hans and his wife Hanni had four daughters and a son, who was born after quite a long gap. HPK made no secret of the fact that he wanted to found a bookselling dynasty. He was obsessed with the family name, and while he waited for the longed-for arrival of Hans Peter Kraus, Jr., I’m sure he regarded me as something of an insurance policy.

I was born in Sutton, outside London, but spent my childhood in Buckinghamshire, not far from Windsor, where my father was a doctor. HPK would often visit us when he was on one of his book-buying trips. He always stayed at The Ritz, and treated me to amazing lunches, when he would summon the dessert trolley and challenge the waiter to see how much he could pile onto my plate. Afterwards he would take me for a walk in Green Park and tell me tales of the book trade. I was put on H.P.Kraus’s mailing list at the age of twelve. Of course I was too young to appreciate the quality of his catalogues, but they still mesmerised me, particularly as so many of his books and manuscripts had belonged to kings and queens.

On one of HPK’s visits, he took me to a sale at Sotheby’s. I sat beside him, petrified of making a movement that might be mistaken for a bid. Meanwhile my uncle didn’t bat an eyelid, but suddenly the auctioneer said ‘£8,000 Kraus’. It was a transfixing moment. During lunch at The Ritz, HPK asked if I had thought about what I wanted to do. I told my uncle that I would love to go into the book trade, to which he replied, ‘In that case, you’re not allowed to go to university, because you will learn a lot about very little. In the book trade you need to know a little about an awful lot.’ I went back to school and announced to my housemaster that I didn’t want to go to university. He said that in that case I should leave, as the final two years were intended for those studying for university entrance exams. I was only sixteen at the time, and didn’t feel ready to finish school. After a little research, I discovered that there was no entrance exam for the Sorbonne. I told my housemaster that I wanted to study in Paris, and he allowed me to continue my secondary education.

When the time came to leave school, my uncle arranged for me to work for Kraus Periodicals before joining his rare book business. The day after my eighteenth birthday, I was delivered to Kraus Periodicals’ warehouse in the appropriately named town of Buchs on the border with Liechtenstein. I hardly knew what a back number was when I joined the business, and it wasn’t long before I discovered that I had zero interest in that side of my uncle’s activities. Eventually I was allowed to move to New York in 1964, where I lived with the Kraus family in New Rochelle, and worked in the neighbouring town of Mamaroneck.

The first thing I saw when I arrived was a gimongous pile of boxes ready to go off to UC San Diego in La Jolla. The scale of Kraus’s institutional business was quite mind-boggling. The San Diego campus had been established in 1960, and was one of numerous universities springing up all over the place. Every day auction and book dealers’ catalogues would arrive from all over the world. Although most of them would not have been of interest to HPK, he would read them assiduously. He spent a large part of the day looking over the descriptions written by his team of cataloguers, pointing out what was of particular importance about each item, like a general commanding his army. Professor Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt was Kraus’s chief bibliographer from 1950 to 1968. He had been Curator of the Rare Book Department at Columbia, and a professor of library studies at some of the universities to which Kraus sold books.

It was easy for Lehmann-Haupt to pack a suitcase of books and go off on a sales trip, as so many of the librarians were former students. When my turn came, I had an incredibly difficult time. I remember setting off to Harvard with a manuscript copy of the Harvard Charter of 1650 in my suitcase. ‘It’s wonderful’, they said, but didn’t buy it. I was sent to Australia with one of the earliest maps of the continent, and a substantial quantity of the original drawings of Gould’s Birds of Australia. I thought it was going to be like falling off a log but, again, the librarians said, ‘It’s wonderful’, but didn’t buy them.

My success rate was alarmingly low and I took every rejection quite personally. It was somewhat humiliating to be a travelling salesman, but on the other hand the feeling was mitigated by the fact that I was handling extraordinary material. I sometimes wonder if my uncle had deliberately planned it that way; it was certainly a great learning experience. During a trip to North Carolina to sell periodicals, I had a road-to-Damascus moment. I was travelling with a colleague, and we had chosen to visit North Carolina as it was full of universities. We sold nothing on the first day, and went back to our hotel where we were sharing a room. My colleague sat on his bed smoking pot, and I sat on my bed wondering how it was possible to have sold nothing. Over the next week things didn’t improve, but my colleague managed to persuade me that there was more to life than working for Kraus. He helped me to change my attitude and, although I still took my work seriously, I no longer took it personally. It was an important step towards becoming an independent dealer.

In 1967 Kraus sent me to London to spend the year in Europe, meeting everybody and learning more about the rare book trade. I already knew Keith Fletcher through my cousin Mary Ann Kraus. They had met when they were working at Yale University on a programme for establishing closer relations between booksellers and librarians. In London, Keith introduced me to his parents who virtually adopted me. Bill Fletcher took me literally by the hand to Zwemmer’s in Charing Cross Road and introduced me to John Zwemmer, who in turn took me to Mr Seligman, another of the great art book dealers.

Kraus had an agent in London called Dr Robert Klopstock, who had been a colleague of Robert Maxwell, the notorious press baron. Klopstock was an incredibly elegant man, who considered it his professional duty to have lunch every day at The Caprice with people of interest to HPK in the world of rare books and publishing. Before my first lunch, Klopstock said, ‘The English drink like fish. You’ll have to drink’. On one of those occasions, I was invited to lunch with Colin Franklin, who was working for the family firm of Routledge & Kegan Paul, of which he became vice-chairman. RKP were the leading Oriental booksellers and publishers, and had a wonderful building opposite the British Museum. Kraus reprinted many RKP publications, and we bought from the antiquarian department, where a man named Robert Sawers was a great expert on Japanese prints.

We had a great lunch and Colin invited me to come down to his country place for the weekend. Within minutes of my arrival, he showed me a complete set of the Kelmscott Press books which he had bought from Maggs, all printed on vellum except for the Chaucer, which was on paper, inscribed by Burne-Jones and Morris for Swinburne. Before my weekend with Colin, I hadn’t heard of the Kelmscott Press. It was a complete revelation for me and the start of our friendship.

The following week I received a call from HPK who wanted me to represent him at a three-day auction in Utrecht, but to do so under a pseudonym so that I would attract less attention. I went over to Utrecht, and explained to the fellow in charge that I was bidding for my uncle and that I would need a pseudonym for the sale. He came up with the name of Smith, and every time a lot was knocked down to ‘Mr Smith’, the room burst into laughter. Towards the end of the sale I bought a copy of the Kelmscott Press Gothic Architecture for myself. It was the first book I had bought since my weekend with Colin, and the beginning of my love for private press books.

Amongst the many things I learnt from HPK was never to bargain. ‘It’s the biggest mistake you can make’ he said, ‘because dealers won’t show you their best things’. We used to buy a tremendous amount of books in Paris where the shops were like Potemkin villages. You would go inside and find nothing of interest, as the dealers kept the best books upstairs, downstairs or at home. Actually I’ve stood next to HPK when he was bargaining like a thief, but it was still good advice. It’s logical to favour customers who will pay the full price and pay on time.

My decision to become an independent bookseller was a long time coming, but the discovery that HPK intended his son to take over the rare books business definitely helped. On my last day at H.P.Kraus in January 1972, we had lunch together and he asked what I was going to call my business. When I told him that I was thinking of using my own name, he replied, ‘There’s only room for one Kraus in the world of books. If you call yourself Peter Kraus, I will destroy you, but if you find another name you will have my full support’.

Later that day I drove up to Northampton, MA to spend the weekend with my great friend Leonard Baskin. I told him that I needed to find a name for my business by Monday morning. Lenny asked me to think of an object in my home that I really liked. I mentioned an Eskimo sculpture of a bear, and instantly he said, ‘Call it Ursus’. I went back to East 46th Street and asked Kraus’s chief bibliographer if he could suggest a logo for my business. He came up with the heraldic device of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, from which he dropped the initials R D, leaving a bear muzzled and chained as my logo for Ursus Books.

That same year I met my wife Evi at a dinner party in New York. It was love at first sight and we were married shortly afterwards. When Evi had our first child, Nicki, she left her job as a librarian at Columbia, and started a highly successful business dealing in decorative prints and watercolours. By the time Evi died in 2015, she had become an important force in the field of contemporary botanical art.

For the first two years I ran Ursus Books out of my apartment on West 22nd Street. I had zero money in the bank but my surname was my greatest asset. Everybody let me sell books for them; I don’t think it was because of my smile. I would cycle around town, see things that I liked, and dealers would reserve them for me while I went back to my apartment to offer them on. Lou Cohen of Argosy Book Store on East 59th Street was incredibly indulgent, and let me sit at the back of his shop, and go through the card index of all the books that were kept in storage in Long Island City.

My uncle taught me that I needed to have a solid and scholarly aspect to my business, as it would be difficult to survive on rare books alone. His money was flowing in from the back numbers and academic reprint business, which enabled him to act like a collector in terms of his rare book inventory. For example, he had a copy of the Gutenberg Bible in stock for a decade while I was there. As I already had a good understanding of art books, I decided to make art reference the core of my business. It turned out to be prescient as I was just in time for the boom in the art market.

When I first met Peter Sharp, the owner of The Carlyle in New York, he collected Old Master paintings. I managed to turn him into a book collector, and he became one of my most important clients. He was one of those rare people with money and taste, and he had space in the hotel to create a wonderful room for his collection. Throughout my bookselling life I’ve tried to show people that a book is not just a spine on a shelf; you can be more imaginative with it. Peter had an enormous library table and shelves from floor to ceiling, on which his books were displayed open, rather like we do at bookfairs.

It was Peter who arranged for me to open a shop on the mezzanine floor of The Carlyle, where I had a magical time from 1983 to 2015. My next door neighbour in the hotel was the legendary Monsieur Marc, hairdresser to Nancy Reagan and the ladies who lunch. I never quite knew who would wander into my shop while they waited to have their hair done. One day a woman came in and said that she wanted to buy some books for her husband, who was interested in French Symbolism. She made a little pile of books by Rimbaud and Baudelaire, gave me her credit card, and went back to the hair salon. She was Mrs Walter Matthau. I always thought he was one of the funniest men ever, but I had no idea that he was also highly intelligent.

One of my best clients was Jay Last, a founding father of Silicon Valley. Jay was a passionate collector of lithography, which neatly combined his interest in technology and art. I owe my fascination with the subject to Leonard Baskin and Colin Franklin, who had introduced me to the beauty of the printmaking process. Jay’s first purchase from me was an album of cigar labels, which I had bought from Blackwell’s on a trip to England. Each label was a small masterpiece of colour printing, and it was easy to appreciate their appeal. The full story of Jay’s love of the history of American lithography is recorded in his book The Color Explosion, published in 2005. Shortly before he died in 2021 at the age of 92, Jay said in an interview, ‘Don’t underestimate how the humanities can make your life a lot richer’. His phenomenal collection of 280,000 items is now in The Huntington Library, to which he also gave an endowment to make it accessible to scholars and the public.

The tradition of philanthropy continues in America, and several of my most important clients have made donations of immense significance in the last couple of years to enable institutions to grow their collections. The thing about rare books is that the money involved is tragic compared to the art world, where everything costs millions. A rich benefactor can do so much good without bankrupting themselves. The role of institutions is hugely important to our business. As long as there are libraries acquiring books for people who need to consult them, I’m optimistic about the future.

At the moment I’m trying to organise my business so that my daughter will be able to keep it going. Olivia is a lawyer by profession, but she offered to help me in the business when my wife became sick. I feel very lucky that Olivia has developed a real passion for books and enjoys working at Ursus. My plan is to get rid of certain categories that have been difficult to sell. I disposed of much of my vast inventory of art reference books some time ago when the internet changed the way in which people access that type of information.

The internet is catastrophic for my business and, I believe, for the rare book trade in general. It wiped out book shops and the opportunity for young people to learn the business in the best environment. Gone are the days when Warren Howell educated an entire generation of booksellers in his shop in San Francisco. The internet also enabled ignorant people to sell books. I’m not sure how many of them know how to collate a book - not many, given the number I order online and then have to return because they’re not complete. When I came into the trade, I was told that Corot had painted 3,000 pictures, of which 10,000 were in America. It won’t be long before people say that Hemingway inscribed 50 books, and 3,000 are online. However if you approach rare bookselling with passion, curiosity and the humility to recognise that you will never know it all, there are still tremendous possibilities out there.

Interviewed for The Book Collector in Spring 2025