The Interviews

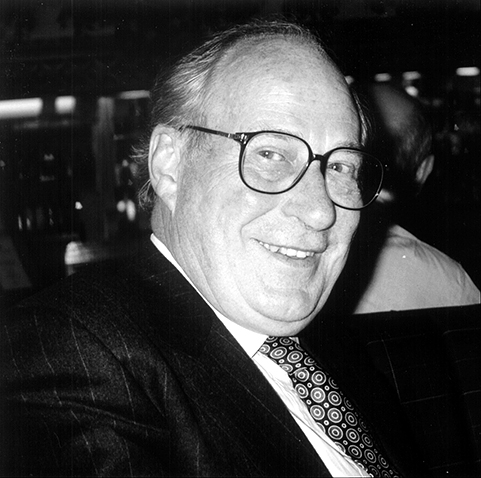

Eric Morten

I was born in the centre of Manchester and breast-fed on my father’s bookstall in Shudehill. It was a famous market for rabbits, hens and books, until the Council closed it down in the ’60s and built a gent’s toilet, or precinct as they call it. My father drank, gambled and fornicated, but he was a good bookseller. As soon as he earned some money, he spent it. As a young child, I had to knock on the door of St Ambrose Presbytery and ask for tuppence so that my mother could have gas to cook with. Many was the time I received benevolence tickets for clothes and shoes from the Bookmakers’ Fund for poor people – while my father kept them in opulence. It never crossed my mind as a child that the book business could make money.

My old man regarded education as a total waste of time. He would take me with him to clear a house and then drop me off late for school. I would be absolutely filthy – black as the ace of spades and in no state to go to school. So he made me wash in the horse trough outside the gates. The head teacher of St Gregory’s Grammar School realised that I could not stand up to my father and that I had no choice if he wanted me to work. By the time I was twelve, I already had a part-time job with Sherratt & Hughes, the big Manchester booksellers, cleaning old bindings in the cellar.

At fifteen, I began to realise that our lifestyle was entirely due to my father’s drinking and gambling. Other booksellers seemed to be doing all right. From that moment I wanted to be like them, have their cars – and not a van – and their style of home. I wanted to be a successful bookseller.

In 1947 I went into the Army and was stationed at Rhyl. Every weekend I came home and my father gave me £1 to work on the stall. Booksellers would come and pick out the better books and I was stuck with the rubbish to sell at one old penny each – twelve paid for my butties and tea and forty-two more paid the day’s rent. To this day I know a book is good if I have never seen it before – I’ve seen all the rubbish in my time.

When I came out of the Army in 1949, I went back to the stalls. I began to develop my father’s business in Shudehill by opening a small shop opposite the stalls. To stop him gambling, I used to hide money away in the bank. On one occasion he turned up in a brand new van. When I asked where he had got it from, he answered that he had found a spare couple of grand in his account so he had spent it before the bank asked for it back. Bang went my fund for expanding into better books.

After ten years of his way of life I’d had enough, and in 1959 I decided to leave the family firm. I had forty books and eighteen quid – it wasn’t going to be easy.... Two people wrote letters to me. The first came from the headmaster of an adult education institute: ‘Dear Eric, please find enclosed a cheque for £5, which I hope is the first of many that you will receive in your lifetime. You’ve done the right thing.’ The other letter came from Bob Walmesley who owned Shaw’s Book- shop in Manchester: ‘Dear Eric, I am telling you to go back to your father now because you will never make it on your own in the antiquarian book trade.’ I have just had a party to celebrate my 70th birthday and I think it’s tragic that Bob was not there to see we’ve made a million.

Tom Crowe was my first customer. He bought a few books for £36, which I spent on several lots in a Manchester auction. Among them was the rare George Moore title, Flowers of Passion, which I sold to Bertram Rota (Julian’s granddad) for £120. This left me with quite a few books, which I sold in Tib Lane market, a short walk away from the hen market. To make extra money, I had worked at night in a pub and it was there that I met my future wife. We got married and had a son, John, but the marriage didn’t work out.

Meanwhile we managed to save £1,200 and bought a partnership in a newsagent’s shop, which gave us some income. At this stage I was doing the papers in the morning, working on the books during the day and waiting in the pub at night – and what’s more I was not ashamed of it. I was determined to show everybody that Morten was a name to be known in the book business.

My father’s books were all secondhand but, simply by having the money, I managed to move up a level into antiquarian books. I went to auctions, chased all over the country, and even advertised in The Guardian, which was taboo for Morten’s – our place was in the Manchester Evening News. One day I received a response from a man whose family owned a big paint business. I went to his house and he pulled two curtains apart and revealed 500 books on the Crusades, which I bought for £90, and took about £500 in a week. There was a gorgeous set of Gibbon’s Roman Empire, which I put in a catalogue. Joseph’s rang to order it but it had already gone to a lady. Joseph replied, ‘Morten, the age of chivalry is dead,’ to which I responded, ‘Not in the north, it isn’t.’

In the mid ’60s I went into publishing and was Seamus Heaney’s first publisher. We were on a roller coaster: 168 titles in twelve years – I even bought a share in the printing works. It was becoming hard work, but booksellers wanted our publications by the dozen – the name of E.J. Morten was becoming known.

Meanwhile I was constantly developing the antiquarian business and starting to buy the properties we occupied. My first premises were between a bicycle shop and a woodwork shop in Warburton Street, Didsbury. I had my eye on moving into the bike shop. As I never seemed to see the owner, I asked my other neighbour to pass on the message that I would give him £100 to move out. The offer was refused and a few months later I increased it to £200, then £300, at which point the woodwork guy said, ‘I’ll move out for that.’ So I took over his shop, and then another one came up next door and, to cut a long story short, I finally bought the entire street.

I had a fantastic solicitor called John Wayne who offered me freeholds and ground rents, and an estate agent who would tell me of any bargains in the investment property market around Didsbury. We bought even when we were broke. They were so good to me and never pressed for the money – and they got paid.

The ’50s and ’60s were wonderful times to be in the trade. Who can talk anything of the Josephs? They were incredible characters. Mortlake, Fletcher, Storey – they were all powerhouses in their own right and knew the book market to the penny. And in the north, there was Charlie Broadhurst, the Kerr brothers, Spelman and Miles, Ellys of Liverpool, and the Halewoods (Harold, Horace and Bill) – still going strong with Harold’s son, Horace, and now his sons. I remember being at a sale in Castleton near Rochdale when Willy Elly stood up and announced to the group of booksellers in the ring that he was now too old to do the knock and was going to pass it on to the youngest one there. That was me and from then on I did the mathematics for them. I’m a numbers man and could do the calculations before the auctioneer got his hammer down.

Over the years people have tried to stop the knock, but of course it still goes on today – only now they knock out before the sale. It will never go away. Ask yourself why you should give your knowledge to someone else for free? Let’s say there are ten booksellers at an auction, all with different buying power. The guy with the money is going to buy the books, and the other fellows go away with nothing. But they have run up the guy with the money because of their knowledge of the books. Meanwhile the auctioneer makes more than 30%, and the booksellers go home with nothing to feed the kids on.

The vendor gives the auctioneer an agency to sell property on his/her behalf at the best possible price that he can achieve. Therefore it is remiss of him to sell it to anybody at an auction if he does not believe that he is achieving the right price. That’s his job. I remember going to the Heber Percy sale in Shropshire in the ’60s. The dealers needed somewhere to sort out the knock. There were about sixteen dealers, all with their own cars, so we drove through the lanes for miles looking for a place to work – it looked like a Mafia meeting. When we arrived at the bus station in Shrewsbury, all looking a bit cheesed, I went up to a bus driver and asked what time he was due out of the depot. He wasn’t leaving for half an hour so I asked if we could use his bus to sort out a little business. ‘All off, please,’ he said to the passengers, as we piled on for the knock. And I can tell you that not just a few were members of the ABA – some of them even became presidents – but a good wash and they were all clean again till next time. Morten’s was a member of the ABA from the ’40s to 1994 when I finally realised that my face did not fit or I did not speak with a plum in my mouth, or whatever it was. It could not have been the ring; too many had been there before me. I travelled the world in support of the ABA – to all the congresses, Japan, the lot.

The PBFA is on quite a different level. The Committee will actually listen to what you have to say, and Gina Dolan, the administrator, is fantastic. To give you an example, there are plenty of people in the trade who are in need of benevolence at some time or another. I like to make sure they get it, whether from me or from the associations that we have belonged to. The PBFA will follow up the needy cases immediately, but the ABA deliberate. Yes, they pay out, but it’s a fight – at least for the people that I have fought for. But it might have all changed these days.

This business is about powering it: you cannot sit in a shop all day and say, ‘OK, I’ve got a copy of Newton’s Principia’. You might make several grand on it, but then what? Of course it’s fabulous to handle great books, but you have to know what to do with the ordinary ones as well. I look at books from every angle and try to see all their different possibilities. Some books may not be saleable, and yet they are still attractive objects – so why not rent them out as stage props? Nearly all the books you see on television belong to me. I fitted out the set for 84, Charing Cross Road, A Room with a View, Brideshead Revisited, Emmerdale Farm, Doctor Finlay, and many other films and shows. One time I bought 450 volumes of The Quarterly Review in original wrappers for £17. A television studio rang to ask if I could fill a solicitor’s office with paper. The Quarterly Review was uncut so we just put the volumes on the shelves back to front and they looked fantastic – at £16 a week, when that was good money. When York University started, the librarian was looking for old periodicals and I sold him The Quarterly Review – 450 volumes – for a tidy sum. I’d kept them for a few years, though. It’s a question of being versatile.

Low Brothers used to bag up their rubbish and sell sacks of books for five shillings. Most people have to pay to get rid of rubbish. Instead they put up posters in mental hospitals all over the country, ‘One hundred books. Guaranteed no two titles alike. Five shillings.’ And family and friends bought them for the inmates to read. You have to make books work for you. Recently I offered one of my best customers a very special book. He had to decline because he had just ordered a new Mercedes and had not yet sold his old one. So I bought his car and he bought my book – two delighted people.

Having said all that, I could not have got where I am today without a fantastic partner. My only regret in life is that I didn’t meet Shirley sooner. She’s had every ounce of faith in me; I ask her advice and she says, ‘Go for it!’ Professor Rogerson at Manchester Metropolitan University has also been of great support. It’s wonderful to see my son achieving the same things. He’s a very popular bookseller and a partner in some of the properties we own. He’s also continuing the film and television business and making a great success of the publishing side. He tells me he’s knackered but that’s par for the course. If a studio rings up and wants a library the next day, you have to drop everything – except your trousers – because the show must go on. But then I’ve been lucky, haven’t I? What a holiday.

Interviewed for The Bookdealer in July 1999