The Interviews

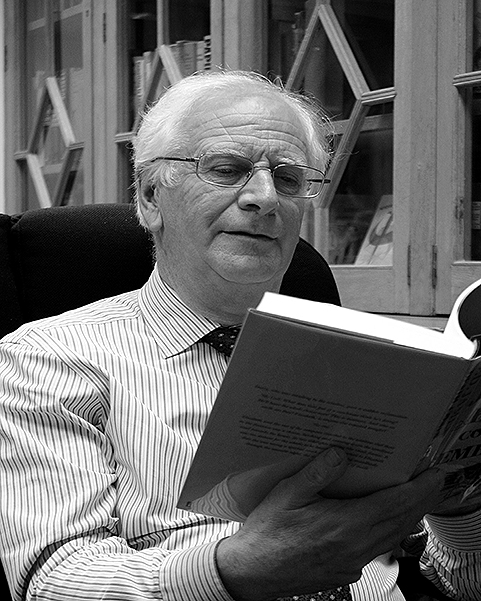

Philip Brown

A Blackwellian is someone who might not be learned himself, but understands the traditions of academia and takes pride in them. The firm is almost like a college within Oxford University. It has given me the opportunity to meet all kinds of interesting people and opened the door to the world of learning and literature. The remarkable thing about the Blackwell family is that it produced three generations of brilliant bookmen – Benjamin Henry, who founded the firm in 1879, Sir Basil and Richard Blackwell. When I first met Sir Basil, he was in his seventies but still a regular presence in the shop. He was always addressed as ‘Gaffer’. Benjamin Henry wanted his son to develop the publishing side of the firm. In 1916 Dorothy L. Sayers became Gaffer’s first editorial assistant. He sensed immediately that she wouldn’t stay very long, remarking that it was like harnessing a racehorse to a plough and, in 1920, she left Blackwell’s to go into advertising, publishing her first novel in 1923. The firm remains in family hands and, although the publishing side has been sold, the chain of forty or so shops continues to thrive as a niche academic bookseller, with shops on several university campuses and a loyal customer base of international alumni.

President Clinton comes back to Oxford from time to time and visits us. He was in the rare books department recently and my colleague took a photograph of him holding a George Washington letter. On one occasion the President asked the deputy manager if he would like him to sign Blackwell’s visitors’ book. No one had any idea if we had such a thing or, if we did, where it was kept. The deputy manager, with great resourcefulness, grabbed the electrician’s book, opened it at a new page and President Clinton signed it. Luckily he didn’t turn back to see who else had signed the book as he would have found a lot of requests to replace light bulbs in the Norrington Room. Bill Clinton’s page has now been removed and framed.

I’m only the fifth manager of Blackwell’s antiquarian department since the firm’s inception. Benjamin Henry originally began trading as a dealer in rare and secondhand books from a tiny room that soon expanded into the main Blackwell’s shop at 48-51 Broad Street. William ‘Rex’ King joined the antiquarian department in the last few years of Benjamin Henry’s life and, after thirty-four years, Rex was succeeded by Edward East and he, in turn, by Peter Fenemore who employed me.

I left Bicester School at the age of sixteen. It was a dreadful place in those days, but I was fortunate to have an excellent English teacher who encouraged my love of literature. I decided to look for a job at Blackwell’s and joined the firm in August 1966. I enjoyed it from my first day. I started with Geoff Neill in the Wants Book department in the newly-opened Norrington Room, the largest room dedicated to bookselling in Europe. My job was to go around the various departments collecting the books for which we had received institutional orders. If the book was out of print, the details were recorded on a five-by-three-inch card, of which we had around 100,000, and advertisements were placed in the Books Wanted section of The Clique. When Geoff Neill retired suddenly, he was briefly succeeded by someone else and it wasn’t long before I found myself running the department. There was something about the whole process that I found very exciting, not least buying something for X and selling it for Y.

In January 1968, Peter Fenemore, who was working in the antiquarian department in Ship Street, asked if I would come and work for him. Edward East was the manager at the time and had been there since 1923. It was very surprising news, as we hardly knew each other, and I shall always be grateful to Peter for giving me the opportunity to become a rare book dealer. Peter gave me an introduction to the gist of things and then I was expected to find my own way. It was a very steep learning curve, particularly as Blackwell’s customers expect the best in terms of bibliographical standards and service. Peter had a particular enthusiasm at the time for private press books and modern first editions, both fields in which condition is so important. While I was learning how to catalogue them, I was also developing my own personal interest in fine printing and book illustration. A Blackwell’s catalogue description should be recognisable by the amount of information it contains, particularly regarding condition. When a customer opens a parcel, the contents should match or exceed his expectations. Dealing with modern books is a good discipline for general antiquarian bookselling, because you have to concern yourself so strictly with condition. It’s best to start with the highest standards; you can always adjust them accordingly.

Not long after I started, Peter became very enthusiastic about the field of transport and technology, and rapidly became a major dealer in the subject, producing a brilliant catalogue (865) in 1969. The following year John Manners joined the firm and began to develop his great expertise in eighteenth-century English literature. John had a wonderful personality and was brilliant with customers. Peter became manager of the antiquarian department in 1971, and we were joined by Derek McDonnell in 1972. Derek is the best bookseller I have ever worked with. He had the ability to take a subject, for example, antiquarian continental books, and develop it from nothing to a substantial turnover within a year. He has a good eye for a book, and can catalogue well, and played to the strengths of Blackwell’s international mailing list. Derek left Blackwell’s in 1976, and John in 1984, both to join Quaritch. As Peter occasionally remarked, Blackwell’s had a tradition of training talented and entrepreneurial rare book dealers. Barry McKay, Simon Luterbacher, Ron Taylor and Karen Thomson have all worked here. By the late 1970s the antiquarian department was beginning to outgrow its premises in Ship Street. Fyfield Manor near Kingston Bagpuize was purchased in 1979 to house the department, and was officially opened in October of that year with a centenary antiquarian catalogue to mark the occasion. Coincidentally, J.H. Parker, the Oxford bookseller, lived at Fyfield Manor during the late nineteenth century. Richard Blackwell was Chairman when Fyfield was purchased. He had a vision of acquiring a beautiful house, not far from where the Blackwell family lived, filling it with rare books and providing accommodation for visiting librarians. It was a wonderful idea, but in practice they tended to roam around the house setting off the alarms and, when the recession started in 1981, American librarians stopped coming over.

John Manners had been fiercely opposed to the antiquarian department’s move to Fyfield, and had given Richard Blackwell a list of seventy-three objections. Meanwhile the building required endless maintenance and, when the roof had to be redone at a cost of £1 a slate, we couldn’t go on throwing money at it. In 1991 we returned to Oxford to premises in Holywell Street, and to the main Broad Street shop in 1999 where the department is now located on the second floor.

Peter Fenemore retired shortly after we moved back to Oxford, and I became manager. I was confident that, with my colleague John King, we could make a success of the retail rare books business. I knew how I wanted to take the department forward but, in the environment of a large company, it was a case of educating the regional manager to the money-making possibilities of rare books. Peter Fenemore hadn’t liked exhibiting at book fairs, and the firm had stopped doing them in the 1950s, although it had been a founder-member of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association, and both Benjamin Henry and Sir Basil had served as President. By the 1980s I was keen that we should start again and, after a number of successful ABA fairs in London, I persuaded Blackwell’s that we should exhibit at American fairs. It took three reports and the arrival of a new regional manager before I was given the go-ahead.

In 1985, the antiquarian department became the first within Blackwell’s to use computers. Today 20 per cent of our business is done on the web, either via our website or, to a lesser extent, ABE. We also send out e-mail catalogues, but our hard-copy catalogue remains the most effective method of selling books. Our best- selling subjects are private press books, modern first editions and science, which is Andrew Hunter’s department. Andrew joined us three years ago and brought his expertise with him, and his knowledge of the institutional market. Derek Walker looks after Classics, which, together with Theology, remain strong subjects for Blackwell’s with its academic tradition. Derek created our website and is extremely talented in all aspects of IT.

The market for private press books is particularly strong in America, and I would always try to exhibit something special at a book fair there – for example, the Golden Cockerel edition of the Four Gospels, decorated by Eric Gill, or indeed anything by the Golden Cockerel Press. My own love of fine printing and book illustration began with the work of Eric Gill and David Jones. Shortly after I joined Blackwell’s I began collecting St Dominic’s Press. When I first started, it was possible to pick up these books, of which many are pamphlets, for as little as £2. However, the prices steadily increased and when I married and we started a family, I wasn’t able to afford to add regularly to my collection. As I always tell people, you should buy books because you love them, not for investment. If you make a profit when you come to sell them, that’s the cream on top.

Sir Basil Blackwell loved private press books and had a great eye for fine printing. In 1921 he rescued the Shakespeare Head Press when it was on the point of bankruptcy, recognising the potential of the typographical genius of Bernard Newdigate. Newdigate produced many beautiful editions for the press – the Froissart (1927-8), Chaucer (1928-9), Spenser (1930), Chapman’s Homer (1930-1), Drayton (1941), and Malory’s Morte d’Arthur (1935) which Blackwell considered Newdigate’s greatest achievement. In 1942 the St Aldate’s premises were taken over by the Americans for war purposes, and all the equipment dispersed – or quite possibly dumped in a skip – including a printing press that had belonged to the Kelmscott Press.

At times my wife Sue has regarded Blackwell’s as the third person in our marriage. I am in love with this job and could have carried on until my eighties. For this reason I have chosen to make a complete break. In April I retired from bookselling after 47 years. I plan to spend my retirement pursuing other enthusiasms, including bird-watching and gardening, but I’ve already been approached by one or two customers who have libraries that they would like me to catalogue. I’ve known many of Blackwell’s customers for over thirty years and friendships have developed. That’s the wonderful thing about this trade; it’s so much more than the simple exchange of books and money.

Interviewed for The Book Collector in Summer 2013