The Interviews

Robert Humm

I belong to the generation of post-war school boys who watched trains. None of us had any money, and train spotting was something that took you out of the house and kept you occupied at zero cost. We lived in suburban Essex and, by the age of eleven, my parents would let me wander around the London termini unattended. As we grew up many of us went into occupations in some way connected with our hobby. We became professional model makers, ran rail tour companies, worked on preserved railways or sold relevant books. We sell our products to each other in an industry, which probably occupies several thousand people.

Early railway literature tended to be aimed at the professional and technical classes. There were of course fine colour-plate books that gentlemen would want to have in their libraries, but throughout the Victorian era the emphasis was on locomotive and civil engineering, and investment literature. A whole range of weekly periodicals sprang up devoted to share issues, prices and prospectuses for new lines. There was no magazine for the non-specialist reader until 1897 when the gap was successfully filled by The Railway Magazine, still going today with a circulation of over 30,000 copies a month.

The publication of the ABC of Southern Locomotives in 1942 was a milestone in railway literature. Ian Allan had the brilliant idea of publishing cheap booklets listing locomotive numbers by region, producing a new one every six months. People were inspired all over the country to organise loco-spotter clubs, and to conform to a certain code of conduct. Allan may fairly be regarded as the father of the train spotting craze of my generation. As we have grown up, the field of railway literature has expanded with us or, I should say, exploded – 75 per cent of all the British railway books in existence have been published since I started in bookselling.

There are not many railway booksellers with shops – there never have been. Most of the people in our field trade from home, and the majority started in the business after retirement. I started bookselling while working for the Ministry of Transport. I was not a born bureaucrat, and wanted to have a second string to my bow. After some rapid early promotion rising to the rank of senior executive officer, my career reached a bit of a plateau. I decided that, if I was going to do something else, I must do it before I was forty. Bookselling has the advantage that you do not need to take the plunge all at once – the stock does not go off or go out of fashion and you can run the business at your own speed and level. I had been collecting railway books in my youth and was familiar with the various dealers and publishers. Norman Kerr in Cumbria was the big wheel in railway literature, although I could rarely afford his prices. He started in the trade as a teenager in the 1930s, and his family are still very much in the book trade. Once I started work in 1964, I had the magnificent salary of £540 a year on which I had to survive in London. It did not leave a huge amount of spare money for buying books. But things gradually built up and within a decade I started selling books as a part-time activity.

The Civil Service was not too bothered about what you did as an outside occupation as long as there was no direct conflict of interest with the Department’s business. I would come home in the evening and then get on with the night job of bookselling. I started producing catalogues, relatively modest publications aimed at private customers and fellow-enthusiasts. I fumbled ahead in a typically British approach and learnt from my mistakes. It was eleven years before I felt ready to take the plunge. My turnover had reached around £35,000 a year. I calculated that I would need to make the leap to a turnover of £60,000 to make a living comparable to my Civil Service salary in the mid-1980s. If I had the whole day at my disposal, I believed that I could make a living out of books. I took the plunge in 1985, within five months of my fortieth birthday.

My father had been a shop keeper and I knew from him what it was like to be self-employed – no staying in bed if you did not feel very well, because there was always the next slice of living to earn. If you went on holiday, you came back to a mountain of work and if you went on holiday too frequently, your competitors might have purloined part of your business. You cannot take a dilettante attitude to running a business. I had a young family to support, bills to pay and a mortgage, and I had to work out very quickly the best use of my time. In my first year of full- time bookselling the turnover hit £70,000. I knew within a couple of years that I had made the right decision.

It became obvious that the family home in West London– a six-bedroom house already bulging at the seams with books – would not be able to accommodate the growing stock which began to overflow into a lock-up garage, a garden shed and, finally, a little shop in Chiswick. Originally intended as a storeroom, we opened the shop and called it The Wyvern after the emblem of the Midland Railway. But none of these arrangements was entirely satisfactory. In the summer of 1985 an advertisement by the BR Property Board appeared in The Railway Magazine stating that part of the Grade II listed station house was to let at Stamford in Lincolnshire. I glanced at it and thought no more, but my wife was keen for us to go and see it.

It was a lovely former stationmaster’s house in Jacobean style, built in local stone in 1848 by Sancton Wood, who built the stations for the old Syston and Peterborough Railway Company. Stamford railway station dates from the first decade of railway mania, when the system mushroomed from being a few disconnected lines to being a unified network.

The house had not been inhabited since the early 1960s, when the stationmaster fell victim to the Beeching cuts. However the station is still operational. The house was in a very poor state of repair and the Property Board offered it to us at a rent which was hard to refuse – those halcyon days are long since over. It took us two years to renovate the building, during which we discovered that it was built like a fortress. The walls are three feet thick in places, and the joists are 15-inch Baltic pine (compared with 8-inch softwood of a modern home) – I have no qualms about overloading this building with the deadweight of 40,000 or so books and periodicals.

Initially I envisaged the stationmaster’s house as more of an office for our catalogue business – I certainly did not write the business plan on the basis of having to attract customers out into the sticks. However, the shop opened for business in June 1987 with no announcement, and people started walking in.

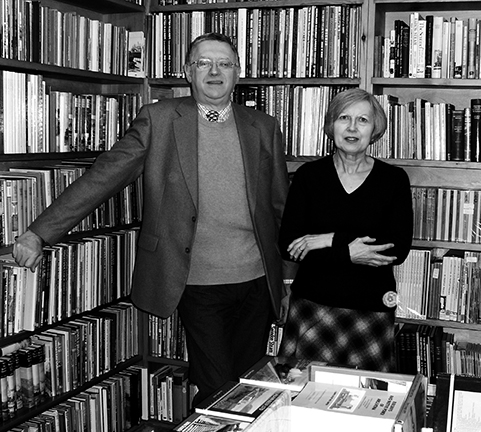

My wife Clare is the ‘& Co.’ in Robert Humm & Co., and has combined the role with bringing up our two daughters. Clare looks after the computer side of the business, running our two websites, managing the mailing list and answering e-mails. She also does the driving, taking me to view collections and attend auctions all over the country. We have two assistants who look after the day-to-day running of the shop. What does this leave me to do? The buying and the cataloguing, meeting customers, and the general administration of running a business.

Nothing beats having a shop. We are fortunate in having very dedicated customers who travel here from all over the world. I am not saying that there is the growth in over-the-counter business that I would like, but it has held its head up and appears to continue to do so. The internet has brought us customers whom we would never have found without it, but it is a very labour-intensive way of selling a book. It requires three or four times the amount of effort compared to selling a book to a customer in the shop.

Our business is very much on the fringe of the mainstream secondhand book trade. We do not belong to a trade association or exhibit at book fairs. We restrict ourselves to two railway collectors’ fairs a year, because we know that they will attract a crowd of like-minded people. I meet my friends, have a good time and the business gets done. I used to buy half of my stock at auction, but the spread of information on the internet has made it impossible to keep a good country sale secret. As time goes by, I find that I buy more and more privately.

The books from the heroic age of railway literature were overwhelmingly technical, for example Nicholas Wood’s Practical treatise on rail-roads, 1825. It is full of algebra, and was devoured avidly by engineers anxious to learn more about this strange new phenomenon. Inevitably the railways became a prolific field for authorship in general. A vast number of guide books to the new railway lines were published – some of them no more than a recitation of what could be seen out of the window.

George Bradshaw’s maps are among the nicer items from the early railway age. Bradshaw invented and published the world’s first railway timetable in 1839. An edition with maps appeared in 1840, and in 1841 the first Monthly Railway Guide, which appeared for 120 years. A map-maker by trade, Bradshaw produced timetables as a way of selling his maps. His hand-coloured railway and canal maps are magnificent examples of cartography. I wish we could get hold of more of them.

There are comparatively few hugely valuable books in our field – the real money is to be made from scarce magazines and periodicals. A complete run of 153 volumes of The Railway Magazine sells for around £4000, depending on condition. I bought a fair number of sets from public libraries when they were disposing of long runs of periodicals. I understand from the publishers that they have no intention of digitising it, and this applies to a number of important periodicals in our field.

My customers are not particularly interested in railway fiction. They do not want to read Agatha Christie on the Orient Express. With very few exceptions, novelists get the railway detail wrong. John Godey’s The Taking of Pelham One Two Three is an exception. Freeman Wills Crofts was an ex-railwayman and he gets the detail right in his novels. I also have a soft spot for L.T.C. Rolt’s fiction. The great historian of engineering and biographer of George and Robert Stephenson, Rolt had served his apprenticeship with a locomotive builder.

When I put thirty or so books from my collection of railway fiction in a catalogue a few years ago, I sold two items. My customers want books on locomotive dimensions, signalling systems, diagrams of rolling stock – what the Germans call ‘Fachbücher’.

I had not intended to stock new books, but they are very important in our field. As in any technical subject, new books are likely to be more accurate, and to benefit from the growing paraphernalia of academic research. They may not be as beautiful to look at or as well written as the earlier material, but the content is likely to be much more informative and reliable. Great Britain, Germany and the United States are the three main publishers of railway books and account for 85 per cent of the subject material published worldwide.

No other country has anything comparable to George Ottley’s Bibliography of British railway history. While working full time for the British Library, he embarked on this monumental project, drawing from his experience in dealing with readers’ inquiries. Although he has his blind spots – he does not cover Bradshaw timetables, for example, or railway guide books or accident reports – his work remains unrivalled in railway bibliography. The first volume was published in 1966, and was followed by a Supplement in 1988, both published by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. A second Supplement appeared in 1998, with around 17,000 entries, published by the National Railway Museum and The Railway & Canal Historical Society. The premier British society for scholarly transport research, the Society became the ‘keeper’ of Ottley’s bibliography after his death in 2006, and publishes extensive book reviews and an annual listing of British railway books and articles.

The railway industry in this country has very little glamour today. The historic stations, the marshalling yards, the locomotive depots – whole thickets of fascinating stuff – have disappeared. When I was a child, there was always something interesting to see out of the window. Nowadays, assuming that you can find a seat that lines up with a window, there is not so much to see; sometimes you cannot even admire the landscape because the railway cuttings have been allowed to grow wild. Locomotive-hauled trains have largely been replaced by look-alike multiple units of one sort or another. Today there are no young children at the end of railway platforms. If there were, they would probably be taken into care. The train spotters are in their sixties – men of my generation who never quite lost the habit of recording things of railway interest. But these days they are probably holding a £3000 camera rather than a shilling booklet.

Interviewed for The Bookdealer in April 2009