The Interviews

Paul Mills

My father was a hydrographer in the Merchant Marine, who settled in Shanghai where he met my mother amongst the émigrés who had escaped from the Russian Revolution. They retired to England in the late 1930s, and my father worked as a chart maker for the Admiralty in Bath during the Second World War. My parents had enjoyed a very different standard of living in Shanghai, and found it quite difficult to adapt to the austerity of post-war Britain. It certainly did not provide the comfortable retirement that they had hoped to enjoy. My father was not in particularly good health, and the opportunity to move to South Africa offered them a better climate and the possibility of regaining aspects of the life which they had known in China.

My father’s interest in books was more or less restricted to H.G.Wells.Whenever he wanted to impress me, he would bring out his copy of A Short History of the World and say ‘It’s all in there – everything you need to know’. My Russian mother meanwhile spent a lot of her life trying to be English, and read Beverly Nichols’s books for guidance on how to achieve this. She regarded Down the Garden Path as the acme of English literature. She rarely talked about her background, and would say that her Russia had disappeared with the Revolution.

My father was sixty when I was born, and was more like a grandfather to me. He died when I was eleven and, although I regret losing him at a young age, we had spent a lot of time together as he was already retired. By the time of my father’s death, we had been living in South Africa for five years, during which the political situation was rapidly deteriorating towards Sharpeville. My mother decided to return to England, where I went to prep school and then boarding school in Dorset.

I would like to have gone to Oxford but went instead to Trinity College, a small liberal arts school in Hartford, Connecticut. My ambition at the time was to study Economics, go to Harvard Business School and rule the world. However a vocational test revealed that I was more suited to becoming a librarian. The Vietnam War was on and I would have been at risk of being drafted if I had attempted to convert my student visa to any other status. I decided to return to South Africa – more to see where I had grown up than with any intention of staying on. In the event I went back to being a student and did a History degree at the University of Cape Town. As it was my second time on campus, I was older than most of the students and not particularly interested in taking part in all the usual activities. I started to haunt the secondhand bookshops around Long Street – initially because I wanted to buy all the books that I needed for my studies, though I now see that my career as a bookseller had its origins in my student hobby.

After graduating I travelled for a couple of years in Africa and India, avoiding as long as possible doing anything more serious in life, but by the mid-1970s economic necessity forced me to turn my attention to some sort of career. Wanting to work for myself, book dealing seemed to offer an interesting opportunity and a way of turning a hobby into a business. I was introduced to Gilly Bickford-Smith of Snowden Smith Books in London, and we began producing catalogues together, which I distributed in South Africa. On one occasion Gilly drew a picture of a Cape Dutch house on the cover of the catalogue and signed it with her initials. I was inundated with telephone calls from customers wanting to buy what they assumed to be an unrecorded drawing by George Bernard Shaw, who had visited South Africa in 1932.

Although the joint venture did not last, it taught me that antiquarian bookselling required less capital to get started than publishing. Originally I thought that bookselling would supplement my earnings from publishing, but it rapidly became all consuming and profitable. I spent the next couple of years working from home, preparing catalogues, mainly of Africana, until 1978 when Tony Clarke made an offer that I could not refuse – a partnership on equal terms in his business, an old established antiquarian firm and thriving bookshop in the centre of Cape Town.

Anthony Clarke came out to Cape Town after the Second World War, in which he had served in the Royal Horse Artillery and won the Military Cross. H.V. Morton tells the story in A Traveller in Italy of how Tony saved Piero della Francesca’s painting of ‘The Resurrection’ on the wall of a room in the town hall of Sansepolcro during a gun battle with the Germans. Although he had never seen the painting, he remembered that it was the subject of Aldous Huxley’s essay entitled The Best Picture. The shelling of the town had already begun when Tony, disobeying orders, commanded his men to stop for fear of destroying the painting. His spur-of-the- moment decision could have had very serious repercussions but, as he learnt later, the Germans had already retreated. Sansepolcro and its famous fresco were saved, and today there is a Via Anthony Clarke in the town.

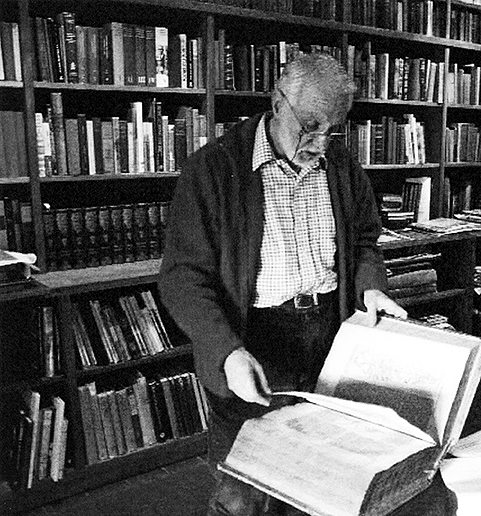

Tony was very much a scholar-bookseller. A correspondent of Graham Greene, who used to order steadily from his catalogues, Tony was extremely well read and ahead of his time in fields such as modern firsts and poetry. His business instincts were guided by his taste rather than by any commercial sense. It was undoubtedly a struggle for him to survive in Cape Town, where the market was dominated by Africana collecting. Tony was not particularly fond of customers, especially when they took his books away, as he described it, or – worse still – mishandled them. If he saw someone pulling a fragile binding off the shelf, he would rush up and announce that it was early closing and bundle the customer out of the shop. Five minutes later, he would look carefully up and down the street, and open the shop again.

Clarke’s was a very traditional business. Tony did not allow a calculator in the shop, and of course there were no faxes or computers. We would catalogue books sitting opposite each other at the same desk. He taught me to be careful about describing a book as ‘scarce’ and would say that the Gutenberg Bible was scarce – everything else was relative. When we set up the partnership, Tony offered to leave his half of the business to me in his Will. He was 63 and I was 33, and so it was reasonable to expect that he would live for some considerable time. In the event I only had two years working with him before he developed pancreatic cancer and died very quickly. Tony never married and was a very private person. I think he would have been extremely surprised by how much affection for him and sadness there was from people all over the world at the news of his death. He had earned a reputation as a bookseller of great integrity, and set an example which I have tried hard to follow.

The 1980s were a time of great change in South Africa. As the country descended deeper into trouble, there was increasing demand from the outside world for books and information on South Africa’s problems. It was a great opportunity for bookselling and, in 1981, I went into partnership with Henrietta Dax, whose background was in the new book business.

Clarke’s catalogues of new books of South African interest began to include government reports, obscure trade union publications, pamphlets, posters and other ephemeral material that was much in demand and difficult to obtain. On our trips to London, we would visit the ANC offices and buy all their publications. These would be shipped to South Africa hidden in the bottom of boxes containing less controversial books. There was always the risk that the censor would open the boxes, and we would be summoned to his office in the port to explain ourselves. At one time it was almost enough for the book to have ‘black’ in the title for it to be an object of suspicion, if not actually banned. The famous example is Black Beauty which was on the list of prohibited books during the Apartheid regime.

The institutional libraries in South Africa were very supportive to us. We had an unofficial arrangement that if we were caught with prohibited material, one or other library would issue us with an official order for it, claiming that it was required for research purposes. It was reassuring to know that a loophole existed, although we never used it. The security police would occasionally visit the shop, instantly recognisable by their short haircuts, square shoulders and general air of never having been in a bookshop before. They would ask in rather illiterate English, ‘You got Steve Biko Student Perspectives on South Africa?’ – hardly a clever trick question – to which we would reply, ‘I’m terribly sorry. It was banned years ago’.

With the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, South Africa embarked on a decade of great hope. The first non-racial elections in 1994, and Mandela’s election as President, were a time of euphoria, almost impossible to describe to anyone who did not experience it. Censorship was lifted and the country moved towards the development of a free press. Incidentally, the censor, finding himself out of a job, told Henrietta in all seriousness that he was thinking of becoming a consultant to the book trade.

In 1999 Henrietta and I decided to go in different directions, and Clarke’s new and antiquarian businesses split neatly down the middle. Henrietta continues to sell new books, prints, maps and some secondhand material in Clarke’s Bookshop in Long Street, while my wife, Janet, and I moved our business, Clarke’s Africana & Rare Books, to our home amongst the vineyards of Constantia where our two children grew up.

Africana has undergone huge changes since the days when the market was dominated by big collectors in Johannesburg spending their mining fortunes. I am told by someone who worked for Francis Edwards that the firm was kept going during the 1930s by South African collectors. Although the collectors today tend to have smaller wallets, their range of interests has expanded enormously. Black writing, ethnography, early photography and anything to do with the natural environment – these are relatively new subjects in the field of Africana collecting. My customers have immense knowledge about their chosen subjects, and it is very enjoyable to be continually learning from them.

The biggest change of course was the coming of the internet, which we were very quick to embrace. I compare the effect to a short-sighted person wearing glasses for the first time and suddenly seeing a whole new world beyond the baffling machine on his desk. I believe that we were amongst the first ten dealers to list our books on ABE. Nowadays there are around 15,000 dealers on ABE and the inevitable has happened – the internet has called the bluff on scarcity and forced the prices down. We try to respond by only listing more unusual items, but selling on ABE is not the future. Some of the books on internet bookselling sites have been there for years. Dealers need to be more nimble and clever in how they sell their books.

One solution for booksellers is surely to hold online auctions. For the past five years we have been running AntiquarianAuctions.com as a simple and effective way to move surplus stock. I am very lucky to be working with my son, Anthony, who is an IT expert and looks after the technical side of AntiquarianAuctions.com, which is still the only dedicated online rare book auction site. We only allow bona fide booksellers to list books, which is an important difference from other online auction sites, and ensures that standards are maintained. Booksellers upload their stock to our monthly auctions under their own names and, at the end of the sale, they deal directly with the buyer. There is an 8 per cent commission charge on successful sales and no buyer’s premium. Each of our sales attracts an average of 100 bidders, based in up to twenty different countries.

As the participating dealers tend to be South African, the auctions have been dominated by Africana. We believe that the future development of AntiquarianAuctions.com is likely to be regional and are seeking dealers in other countries to work in partnership with us. The cost of money in modern times means that for most businesses large holdings of stock are no longer viable economically. We must move with the times and not attempt to protect what is past. Antiquarian bookselling can be profitable with far lower costs than before – but only if we adapt to the new reality.

Interviewed for The Bookdealer in December 2010, and published in The Bookman, No.1, 2011-2012